The Fix: Why Jake LaMotta Threw His 1947 Fight With Billy Fox

June 14th 1960. A warm summer’s day in Washington DC. Former Middleweight champion Jake LaMotta is in town.

He is present at the request of the State Senate Sub-Committee on Anti-Trust and Monopoly in Professional Boxing, an endeavour led by Tennessee’s tenacious Senator, Estes Kefauver.

The Senator is keen to question LaMotta, specifically about his fight with Billy 'Blackjack' Fox in ‘47 and the wider influence of the Mob in the fight game. It is part of a wider Congressional initiative to expose and destroy the infiltration of organised crime into American business.

Boxing had been fertile ground for the Mafia. Enormous criminal empires had been built on the supply of illegal liquor during the Prohibition era. Al Capone’s the most infamous among them.

When prohibition came to an end in 1933, after more than a decade of lucrative and bloody endeavour for the Mob, they needed something new. Access to the machinery of boxing, a wilfully unfettered anarchy still ripe for abuse today, proved remarkably easy to acquire.

The nature of a one-on-one sport, as opposed to the team sports of baseball and football that the country obsessed over, is inherently more malleable to the whim of those looking to control boxing betting markets.

👀Why Jake LaMotta threw a fight with Billy Fox and paid the Mafia $20k for the pleasure pic.twitter.com/gICJzUjCJV

— Gambling USA (@Gambling_USA) October 25, 2019

The scandal that followed the Chicago White Sox in 1919, when they were widely believed to have thrown the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, though they were found Not Guilty in court, was sufficient evidence of the pitfalls present in infiltrating team sports that it has, as far as public account shows, discouraged subsequent interference.

Boxing was different. Exert control over one participant and the mob could dictate outcomes. If the meritocracy of who fought who could be controlled too, as it was in the post war era when connected men bought up the rights to the major venues, then manipulating the sport to suit betting syndicates became ever easier. Championship boxing became a closed shop.

Two decades on from the Kefauver hearings, as they would become known, LaMotta was pealed from the noir pulp post war American culture consigned him to, and the truth of a hermit’s existence in 1970s Florida, to be the muse for Martin Scorsese's 1980 Raging Bull biopic.

A piece of such searing ferocity and unabashed truth, that LaMotta’s renown grew as a result and he would, perhaps unjustly, become the face for all that was wrong in boxing in the 1940s and 1950s.

The son of an Italian immigrant and encouraged to fight by his Sicilian born father, often against older children, and for money, LaMotta grew up in the Lower East Side, the toughest area of New York and a melting pot of immigrant cultures and poverty.

His life was a battle long before he embarked on his boxing career in 1941 aged just 19. LaMotta fought the last of his 106 professional contests in 1954, a tired fighter and a shadow of the man who bested Fritzie Zivic and whipped Sugar Ray Robinson in 1943.

In 1960, he was six years into a retirement that had, unsurprisingly, offered no more contentment, in the places Jake had pursued it at least, than the purgatory of his battles in the ring. A six-month stint on the chain gang in ‘58, the punishment for introducing men to an underage girl at a club he ran in Miami, something LaMotta would strenuously deny, had further blackened his reputation.

Those who had seen him climb the steps to the Senate building that morning noted he was heavier, slower and looked every day of his 37 years. Only a solitary ‘Hey champ’ broke through the hubbub of a normal Tuesday morning in the wide, airy corridors within.

This was an unusual stage for the kid from the Bronx. A battle of wits, wrestling for ownership of the truth with men of learning, rather than his comfort zone of a primal battle of wills, of perseverance over pain, with some other grown up kid from the slums.

The Kefauver Hearings

LaMotta, the headline act at the Kefauver Hearings, would describe his current occupation, in all seriousness, as, “Actor”. A Freudian clue for the gathered inquisitors judging his performance but reflective of a genuine post fight career Jake was pursuing, one that peaked the following year when he appeared as a bartender in ‘The Hustler’ starring Paul Newman.

Jake was never cast as the romantic lead or the ‘hooker with a heart of gold’, even in his own story. People didn’t pay to see his guile, his flair, pathos. They came to see the monster, the unrelenting, unrepentant all-action wrecking machine.

It wasn’t an affected persona. A fact Scorsese would play with in his critically acclaimed study. Despite the physical prowess of his prime, the thick Italian locks and a parade of beautiful women suggesting otherwise, he was, for most of the people he encountered, the villain. A dark cloud. Not the sunshine and rainbows of the honourable pugs more commonly depicted on the silver screen.

On that balmy June day in 1960, those truths were not yet known, other than to those who lived through the reality Scorsese tried to capture. Within the marbled coliseum of the third floor Caucus Room, and to a watching America, he was still Jake LaMotta, the man who fought Sugar Ray Robinson six times, becoming the first man to beat him in one of sport's best ever rivalries.

There remained many who couldn’t reconcile The Bronx Bull, as he was known during his professional career, ‘going into the tank' for money. That he would ever ‘lay down’ seemed unthinkable, given his defiance at the fists of the great Sugar Ray in their final bout; one which became known as the St Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1951, such was the beating LaMotta sustained.

LaMotta pulled back the chair. The television camera tracked his steps, his famous face loomed into view. The room fell silent, save for the tick of a clock toward 10.15, the hum of the ventilation system and the feint click of shoes as clerks and typists filed back from their coffee break.

A final figure stole through the closing door, the draft parting the smoke that swirled from a baker’s dozen of ash trays and proceedings commenced.

For those watching on television and in the cinemas hosting screenings, it was a familiar setting. The room had history of its own having provided the backdrop to the Titanic enquiry in 1912, and the watching public had seen the testimony of Jimmy Hoffa in 1954 and, just five months earlier, John F. Kennedy announce his candidacy for the presidential elections from within its walls.

‘LaMotta can still put bums on seats'

As it had been for those tumultuous events, the room was filled beyond its capacity. Nat Fleischer, Ring Magazine Editor, who would eventually be called as an expert witness in the hearings, may have scribbled that ‘LaMotta can still put bums on seats.’

Adrenalin bristled beneath the surface, like an old friend LaMotta embraced its familiar warmth. A wry smile threatening his lips.

He flattened the breast of his suit, as if preparing to eat, and sat. The creases of his tailoring stretched to the insulation he'd gathered in the decadence of retirement. His oil black hair had thinned, whispering middle age, his iron jaw had been absorbed like melting wax into his thick neck. The proportions of which were exaggerated by the narrowness of his wise guy tie and the starched white noose of his collar.

His fingers interlocked. His arms, bent at the elbow, laid heavily on the rich, mahogany table. A brooding morass. His face wore the costume of penitence, but the cocktail of arrogance and fear were barely concealed beneath, LaMotta ran over the lines he’d practiced. Reminded himself of the traps and feints they would lay. Physically, LaMotta couldn’t disguise the conflict within, his body half-cocked between a familiar boxer’s guard and that of a tentative child kneeling for his first communion.

A dangerous man, in and out of the ring, LaMotta was rendered helpless by the process and the impending dissolution of his character. The one he had earned for himself in the ring, under the lights. The one that meant something. To him at least. Not the one veiled behind the curtains of domesticity.

The truth of who he really was had long been revealed to those who knew him, those he claimed to love. Contempt, and the suppression of fear, furrowed his brow. Narrowed his dark glare. He was frustrated by his lack of options. Of being told what to do. Of not being able to hit that which he must overcome.

Most of all, he was uneasy in another man’s world. ‘These grey faces, these briefcases, these ‘regular Joes’ would never dare to tread in mine. They didn’t understand boxing. The streets. My world.’

He looked toward the faces of the commission, Senators Philip Hart and Kefauver central, flanked by legal counsel John G. Bonomi, and swallowed hard. A small piece of folded paper appeared in his hands, unconsciously he toyed with it, like a wistful bar fly drinker with his last dollar.

He was alone. No cornerman. No brother in arms. Nobody urging him on. He took a sip of water, the glass cradled delicately in his right hand. A right hand that had clubbed countless contenders to defeat but one surprisingly small, the hands of a painter not a prize fighter. He waited for the questions.

He knew confession was his only path to absolution. But the words burned. The reality hurt. He would explain, ‘Make these city boys see. It wasn’t fear. It wasn’t cowardice. It wasn’t even money. It was the only way. The only way to get my shot. What was mine. I’d earned it. Nobody would give me a chance. Five years as the uncrowned champion. I deserved that shot. I did what needed to be done.’

LaMotta tried hard to justify his actions and would tell the commission, “I’m not afraid of none of them rats!”. It was a forlorn punch from a man on the ropes, playing to the cheap seats, scared of the darkness, of what defeat, the truth, could mean. The terror wrought by those that Hart and Kefauver were really in pursuit of, was evident in the precision of his other responses.

Revisions in his story from pre-trial statements, the vagueness, the selective amnesia and loudest of all, though some of his answers needed to be repeated to be audible, the denials about the people involved in organising the fix.

Notorious Characters

Names like Frankie Carbo, Frank ‘Blinky’ Palermo and Gabriel Genevese. Notorious and connected men who made things happen, organised title fights, and, when things went wrong, made problems, obstacles, ‘rats’, disappear. Men with hearts blacker than their overcoats.

LaMotta was sincere in his justification, that he only did it to get a shot at the championship, that he had turned down more money to lose to Tony Janiro months before he agreed to lose to Billy Fox.

He lost the fight with Fox in exchange for a fight with Marcel Cerdan, the Middleweight champion and had paid $20,000 to sweeten the deal. It was a story he would repeat until his death in 2017, aged 95. Still belligerent, but with the rage dulled by time, seven wives and the accrued humility of old age.

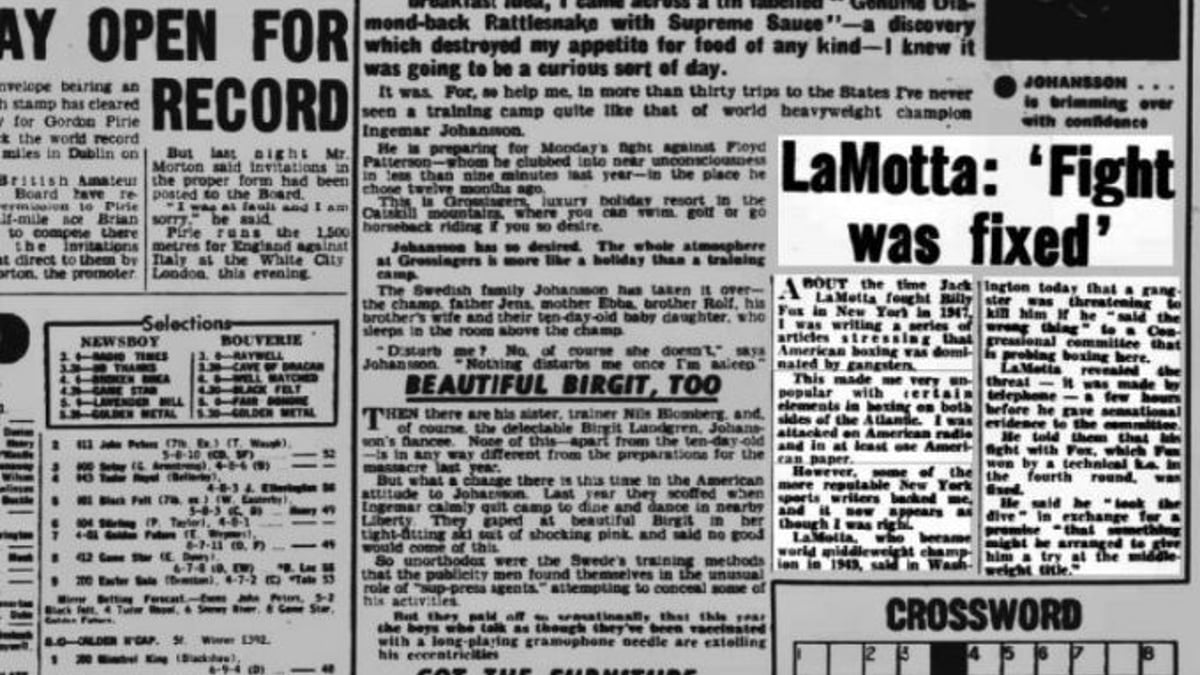

No matter the sincerity of LaMotta’s performance, in the end, the answer that would glow in the history books, in the folklore of boxing and into the living rooms of America in 1960, had to be uttered.

Bonomi: “That’s the truth, you faked the knockout, is that correct?”

LaMotta: “Yes sir.”

And in those two words, though their significance was not fully appreciated at the time, the racketeering and organised crime machine that ran boxing, in the mafia guise with we most associate the phrase, began to unravel.

It would take enormous courage from those same ‘regular Joes’ that LaMotta felt such contempt for, but the world he had inhabited, alongside illustrious greats like Ike Williams, Rocky Graziano and Joe Louis, would finally be dismantled.

Until then, LaMotta and the world of championship boxing in America in the post war period, and possibly as late as Sonny Liston’s fight with Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) in 1964, was governed by the Mob.

Few refused the offers or were able to prevail without their good will. LaMotta’s great nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson was a singular example. Though even he, with middle age approaching and with unpaid tax bills mounting, was forced to smile and dance to order in the end.

In 1947, Jake ‘threw’ a fight with Billy Fox.

He did it because the reward for doing so, a shot at the title, was the offer he couldn’t refuse.

Stay In The Loop With Free Bets, Insider Tips & More!

Live Betting. Sports Promos. Sent Weekly.