Biometrics: Currency, Conundrum in Sports Betting Future

The prospective American sports consumer of the near future has settled into his seat ten minutes into an otherwise uninspiring midweek game. Traffic was wretched, the visiting team not worth the speeding citation.

A $16 snack on his lap, a $12 beer in the holder, he checks the score and notes the players angling toward his end of the arena as he draws a smartphone from his jacket.

A few taps bring him to his app of choice. A few swipes cue up the game before him as digested by the world beyond this downtown arena. Another swipe immerses him in the augmented entertainment reality that legalized sports betting has borne.

So many choices.

Next player to score. Boring.

Next to shoot? Too random.

And then, he’s on to something interesting. Interesting for bettors, but among the more worrisome aspects of legalized sports betting and professional leagues’ embrace of it as a revenue stream: the collection and dissemination of advanced player data, including so-called biometrics, as fodder for betting markets.

“Some people envision that someday people are going to be betting on biometric data,” a source requesting anonymity told Gambling.com. “You know, what is [Alexander] Ovechkin’s heart rate going to be right before or right after he scored a goal?

“On one hand, personally, I think we're a ways before we get to that point. But it's in sight.”

Legality, Ethics, Business Await Guidance in ‘Wild, Wild West’

The example is possibly far enough to the edge of current morality and technological boundaries to not be pressing. Professional sports leagues and gambling interests have more immediate priorities following the repeal of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act.

But in a global sports betting market worth as much as $40 billion annually, it will eventually become a major topic in the United States. And given the way that sports and wagering enterprises are impacting the other in a society in which personal information is rapidly – by choice or the consequence of convenience – becoming public domain, it is not implausible that bettors could find it not only acceptable but entertaining to wager on pulse rates or testosterone levels.

At the legal, ethical and mercantile nexus of all of it is biometrics, which is understood as the biological and behavioral characteristics that identify an individual. That can include everything from fingerprints to retinal structure to pulse. It can be used for security, or business. Or perhaps, entertainment.

With case law yet to catch up to technological capability and billions in play for sports leagues and sportsbooks, an athlete is likely to lose their rights as a private individual before clarity is attained, Barbara Osborne, J.D. Professor, Exercise and Sport Science and an adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina law school told Gambling.com.

“This is literally the wild, Wild West,” said Osborne, who co-authored a 2017 Marquette Sports Law Review paper entitled ‘Legal and Ethical Implications of Athletes,' Biometric Data Collection in Professional Sport.' “We have no idea what's going to happen until it happens and then we'll be scrambling to fix it.”

The athlete, Osborne stressed “is the loser once their physical privacy has been completely obliterated.”

“You have to have law in order for precedent to be set,” she said. “And I think that basically there'll probably be some landmark scandal which will crystallize things and I'm guessing somebody will have to be a victim in some way for people to stand up and pay attention and say, ‘That's not right.’”

Pro Athletes Gaze Wary Eye at Their Heart Rates

Professional athletes consider their health data a last bastion of privacy even as they live and perform in an ever-widening public domain.

Clarence Nesbitt, general counsel of the National Basketball Players Association, said during a Nov. 15 hearing on sports betting that National Basketball Association players consider biometric information “our data” and not something to be collectively bargained over with management.

“[We] would like some legislation clarifying that between us and the league. That is not yet a settled matter,” he said. “But with these new forms of data and these new data streams, we would think player consent is necessary. And the best way to make sure that voice is heard is by giving us ownership of that data.”

Nesbitt said he preferred federal, but accept state-level, legislation to settle the matter because of “the risk that some valuable ownership right like that could potentially be lost in collective bargaining.”

“Remember,” he added, “it's bargaining, so you have to give something to get something.”

Casey Schwab, vice president of business and legal affairs for the NFL Players Association concurred, asserting that “our players own their data. So, one side of it is protecting the privacy of our players’ data. The other side of that coin is consent, which sometimes comes along with commercial opportunities.”

Schwab said the last NFL collective bargaining agreement didn’t and couldn’t have accounted for advances in sports technology.

“In 2010, when that was being negotiated, nobody was thinking about compression shorts that can track your rate increase in your metabolism or metabolic rate,” he said. “Right now, we're thinking about those things, and it, of course is relevant for betting, but it's also for media. You see Sportradar sells this data out of the market and it's not just for betting. It's for media and content.”

National Hockey League Player's Association special counsel Steve Fehr said the exploitation of biometrics data is one of many he considers "potentially very problematical."

"But we can't hold back time and we're not going to be able to completely stop it," he said. "So, we're going to have to figure out how to deal with it and we certainly don't have all the answers today. And I think anybody who thinks they know what this is going to look like five-to-10 years from now is kidding themselves."

The Australian Football League allows limited betting on five "metrics," but the practice is unpopular with players, said Simon Clarke, its senior manager of wagering and major projects.

"That's something that we’re looking at, in preparation for in-play mobile bidding," he said. "The challenge with us is that our players association don't like betting on anything that's conceived as a negative. Our players run about 15 to 20 kilometers in a game, 10 to 12 miles. If the next week they drop down to half that, then the players association don’t like that. Then there’s discussions about their form, their contract renewals and so forth. So we're currently limited to the top five, betting on the top five metrics, most distance covered, high speed in the game and so forth."

Genius Sports Exec Says Bettors Won't Embrace Biometrics

Jack Davison, chief commercial officer for Genius Sports, a technology and data merchant that last week signed a distribution with the NBA, doubts the betting public will embrace wagering on biometrics, however.

"I think from a market point of view there is definitely interest, from the media market, from a consumer point of view, from an engagement point of view. This stuff is really, really, really interesting," he said. "From a creation of betting market, I think it's less so. I think the consumer has a bit of a trust issue.

"They want to bet, typically, on things that they can see and they can see the outcome of themselves. Now, you can't see someone's heart rate. It's a slightly different question. I'm not saying there's not interest there and there's loads of issues around whether they should be shared for lots of different reasons, including the stuff that Simon's just outlined, but from a betting market, it's not there currently. ... It doesn't drive lots of handle."

Data Is Commodity As Leagues Strike Wagering Deals

The NBA has signed its first betting data partnerships in the U.S., announcing partnerships with Sportradar and Genius Sports to begin this season. The companies will assist the NBA in providing official NBA data to licensed gaming operators.

— Alicia Jessop (@RulingSports) November 28, 2018

Professional sports leagues and the National Collegiate Athletic Association were united in opposition to legalized sports betting before May. But when offering legal sports betting became the province of state legislatures after the Supreme Court struck down PASPA, these organizations began leveraging themselves for a windfall.

While these leagues were rebuffed in their attempts to negotiate taxes on wagering handle first deemed “integrity fees” and then "royalties" from states like New Jersey, Delaware and West Virginia as they instituted legal sports betting, the concept of selling official data in marketing deals with bookmakers seeking unique new gaming options soon rooted.

The NBA, which initially proposed a 1-percent integrity fee concept last year during a hearing on prospective gambling legislation in Indiana, was the first to pivot, inking a multi-year deal in July with MGM Resorts International as official gaming partner.

The agreement allowed the league to profit from its intellectual property, including official data. In November, the NBA added Francoise de Jeux as its first European wagering outlet. It announced deals with Sportradar and Genius Sports on Wednesday to distribute real-time betting odds to sportsbooks.

The National Hockey League signed a similar MGM deal in October and has since announced a data accord with FanDuel. As part of the MGM agreement, the NHL will begin providing “enhanced data and analytics” next season for wagering content.

Privacy laws would seemingly preclude biometric data from inclusion because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act laws designed to safeguard medical information. But there is, as Osborne notes, no case law particular to the issue.

But a first step to it might have been taken in October when the Indiana State Supreme Court refuted the claims of former NCAA athletes who sought $5 million in damages and alleged FanDuel and DraftKings had no right to use their likenesses without consent. The court dismissed the claim, according to an opinion written by Justice Steven David "because the use falls within the meaning of 'material that has newsworthy value,' an exception under the statute."

Likeness and statistics are not heart rates and oxygen levels, but differentiated each of the three plaintiffs. The National Hockey League Players' Association is the next major player union set to negotiate a collective bargaining agreement, with an opt-out possible in September, and the NBPA might have provided a model entering negotiations.

“The NBA was the only league from a collective bargaining perspective to really specifically address the bio data stuff,” Osborne said. “Everything else was tangential relative to either medical information or physical information. And so, as the new collective bargaining agreements get ironed out, I think this will be an area that's going to have to be spelled out and one of the reasons I think that the leagues have tried to avoid it is because they don't want to have to get into the issue about who owns the bio data.”

What is For Sale, What Does it Mean?

NHL deputy commissioner Bill Daly told Gambling.com that the league has no plans to provide biometrics health data for sports betting, but acknowledged the difficulty in differentiating it from game data.

“There's some gray areas between the two, but I'd draw a distinction between the personal puck-tracking data we (will offer) and personal biometrics,” he said. “In the short term, we want to separate them to the extent that we can. Longer term, I can't see a public case for us offering biometrics of our players."

But the information is increasingly within reach. Major League Baseball and the National Football League players’ associations have partnered with “human performance optimization company” WHOOP, which can capture data in-game, a collaboration described as “unprecedented” in Osborne’s law review paper.

MGM announced a sponsorship deal with MLB on Tuesday similar to previous pacts with the NHL and NBA, giving it access to troves of statistical information including future exclusive access to “enhanced” data.

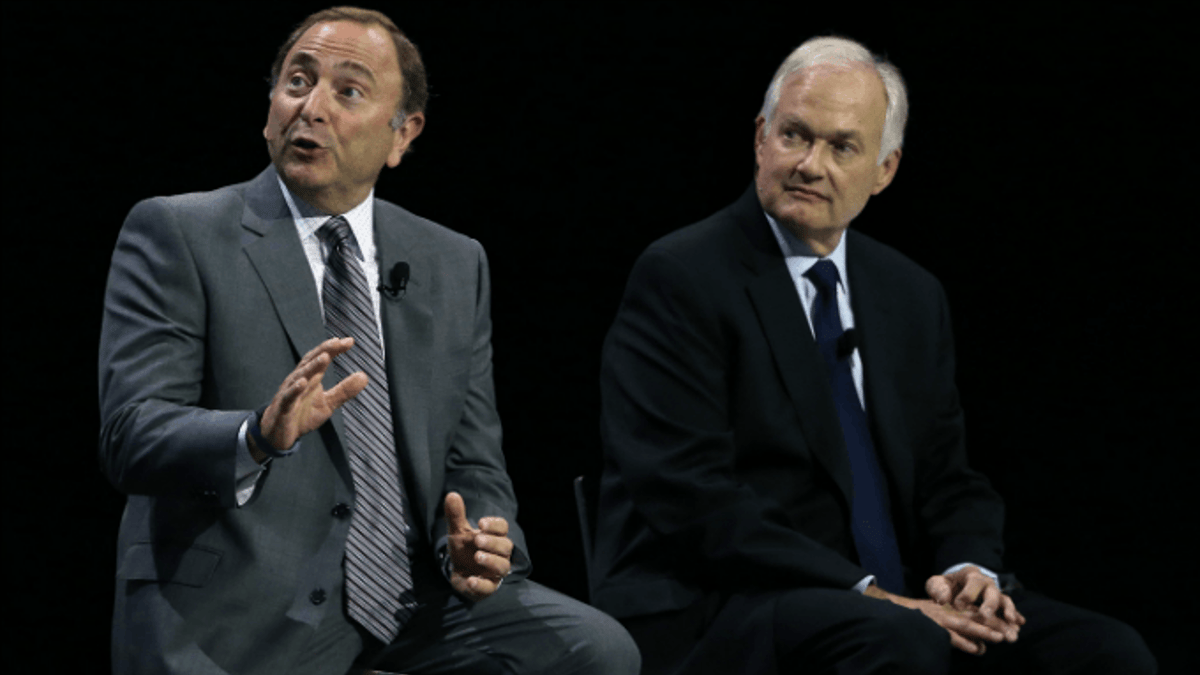

While athletes and their representatives have generally loathed the concept of in-play wagers for various reasons, the NHL’s Gary Bettman (above left) and NBA’s Adam Silver have seemingly accepted it as a concept and MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said baseball’s slower speed of play “gives an opportunity to be creative with respect to the types of wagers” possible between pitches.

That type of wagering would not necessarily involve biometrics, although reduced bat speed or velocity on a slap shot could hint at the health of an athlete. The question is whether that is in the public domain if played out during competition.

But Osborne said converting biometrics into gaming options would be relatively simple. There could be bets on breathing rates, testosterone levels as measured through sweat. It would all depend on owners, she said, who “want to monetize anything they can because the cost of doing business continues to rise.”

“Think about it like in a soccer game where there's a penalty kick and the guy has to step up to take the shot. It would be really, really easy to make a 'high' or 'low' on what's his heart rate when he takes the shot,” she posited. “And that's not just about the heartbeat thing. Now that affects whether he makes it or does he not, and people are using that data to decide whether or not they're going to bet which way."

Ted Leonsis, principal of Monumental Sports & Entertainment, which owns multiple Washington, D.C. sports franchises including the Stanley Cup champion Capitals, Wizards (NBA) and the Capital One Arena in which they play, has been an early and vocal advocate of integrating sports betting into an analytics-driven new strain of sports entertainment. He has no interest, he said, in “being in the gaming and gambling business on the handle. We want to be the content generator, the environment that is producing and providing the data, giving the streaming, giving the access and having consumers trust what we do.”

Biometrics Data an Exploitable Resource for Unscrupulous

But data doesn’t have to be offered to be exploited. The “average hacker,” Osborne said, would struggle to decode proprietary algorithms of encrypted biometric data gathered by professional leagues through tech companies. But access to this information could be priceless if acquired.

“I see the potential for problems in gambling, in daily fantasy. I see it as a problem for all those little one-offs, gambling-kinds-of-things that they could do the instant stuff on,” she said, “if some of these biometric data shows that they're coming back from injury and they're really only at 75 percent and people have access to that information.

“Is it going to change whether they play, they don't play, how you bet them, how you choose them? Having access to that data versus ‘so-and-so's been cleared to play’ and that's all, having access to the information that is going to matter, it could be used for good, but it can be used for evil equally well.”

Biometrics Seeping into Sporting Culture in Various Ways

It was used for entertainment and analysis in the New York City Marathon on Nov. 3 as 10 runners wore a small device used to collect biometric data including heart rate, skin temperature and breathing rate.

It was used in an attempt to exonerate professional cyclist Chris Froome attempt to exonerate professional cyclist Chris Froome in July when Team Sky released a trove of dating include the four-time Tour de France winner’s diet, power output and heart rate during his Giro d’Italia win in May. Froome had just been cleared of doping charges stemming from asthma medicine found in a urine sample after he won the Vuelta a Espana in 2017.

Team Sky presented the data to bolster claims he had used legal levels of the drug salbutamol during both races without enhancing performance.

And biometrics were used by Russian hackers in 2016 in an attempt to undermine the World Anti-Doping Agency’s policy on “therapeutic use exemptions” for certain banned substances by releasing medical records. In the process it made public the private health records of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams and Olympic gold medalist gymnast Simone Biles.

And still, no legal clarity.

Osborne speculates that a Williams- and Biles-like case, but on a larger scale, will eventually help establish ethical and commercial boundaries that do not yet exist.

“It's going to be more like a beloved athlete had some horrible thing happen to them and it was exposed to everybody and people didn't like the fact that he was harmed in that way,” she said. “When you're testing blood samples and stuff, the information that you can get from that, it goes way beyond whether or not you're taking performance-enhancing substances,” Osborne said. “And so, a female athlete that's pregnant may not want that information disclosed until she has to disclose it. An athlete with a sexually transmitted disease might not want that exposed. And the athlete that has HIV might not want that exposed.”

Now What? Athletes and Leagues Will Know When They Know

David Foster believes he has the answer. As deputy general counsel of the NBPA he's in a position to help enact it. Players, he insists must maintain control.

"It's going to be our job to make sure our players are fully educated, they understand the risks and if they're not comfortable with everyone in the world knowing their heart rate when they're at the free throw line or exactly how much they're sweating, then we will fight against it," he said on Wednesday. "If the players are comfortable with the world having all that information, then we will engage in talks about that. But it's information that's being generated from their bodies.

"They need to make that decision."

And hope no one else makes it for them.

Stay In The Loop With Free Bets, Insider Tips & More!

Live Betting. Sports Promos. Sent Weekly.